When your passion and profession is photography, you know things have gotten pretty bad when you put the camera away with no intention of taking it out again. That is how I felt for a relatively short, but very vivid time of my life. I was in the middle of a travel adventure and my situation was spiraling down at a rate that I couldn’t control. A series of mistakes, a few bad assumptions and a little bad luck left me more concerned about how I was going to make it out of it alive and less concerned about making great photos. This was a real-life travel adventure.

Alaska Bicycle Adventure

It all started back in 2003 when my buddy Tim and I went on our Alaska bicycle adventure. The idea was to cross the state from south to north, starting at the edge of the Pacific Ocean and traveling 1500 miles north before ending up on the shores of the Arctic Ocean. This wasn’t our first rodeo; we’d previously spent 6 weeks circumnavigating Iceland. We were used to the work, the climate, and were pretty good at making rational safe decisions, or so we thought.

Our route was well planned before we left home, but while traveling to our starting point we came upon a newspaper article describing the beauty of a 40-mile trail that paralleled our expected route. We thought that, since we had mountain bikes adapted for touring, it would be nice to get them off the pavement and into the hills. We were both carrying cameras and documenting our journey for an expected travelogue that we would create afterward. This mountain detour seemed like a great plot twist that would provide an interesting addition to our Alaskan adventure.

At the Anchorage Airport we picked up a visitor guide that led us to the resurrection trail.

The travel adventure begins

The sign for the Resurrection Pass Trail doesn’t exactly point you in the right direction. The problem was that Alaskan highway signs are placed about 50 yards before the actual road or turn. Cars traveling at highway speed would then have a few seconds to slow down. The issue with this sign is that while is was the standard 50 yards before the correct turn, it was also exactly lined up with an unnamed logging road. From our bicycling perspective, we saw the sign, stopped to look at it, then turned in the direction it was pointed and saw a road. The road it pointed to looked like any one of a hundred gravel roads that we’d been down before in route to a hike.

The sign that led us astray; the actual road we were supposed to take is 50 yards to the right.

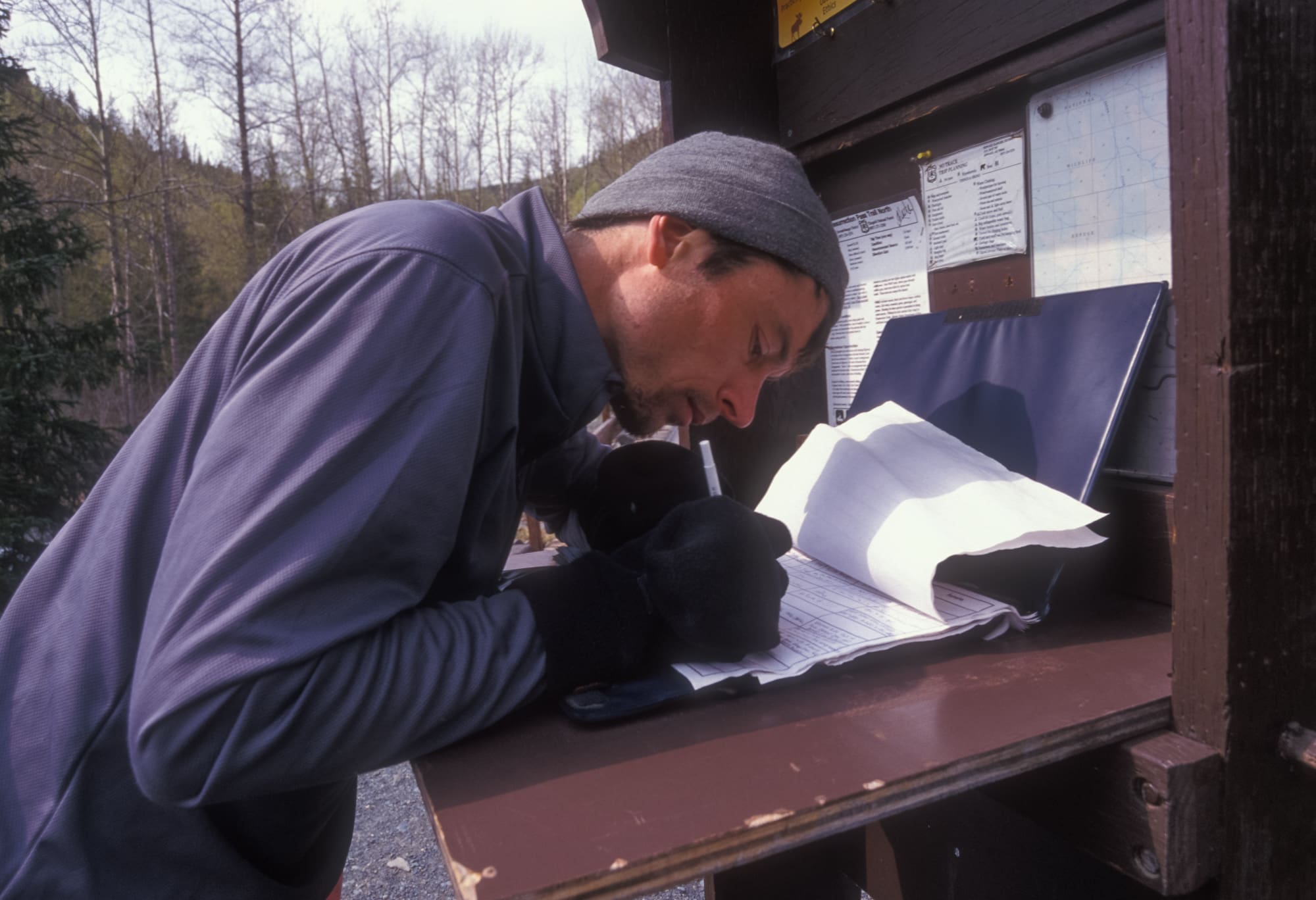

As we headed up the wrong road, apart from the initial road sign that we followed, we did note the lack of additional signage but shrugged it off. While the road didn’t seem exactly right we couldn’t imagine how we might had made a mistake; after all we even took a photo of the sign with us heading up the road. With no parking lot, no registration box and no port-a-potty, we figured Alaskans were just rugged and a bit different.

A small foot path at the end of the road soon petered out into a musky bog, thick with mosquitoes. At this point we knew something went wrong. From our basic maps we determined that we must have taken the wrong road and that the true trail was to our east. We climbed trees to scout the route, pushed our way through the thick bush, and carried our 100-pound bikes through the forest for a few hours before finding the true trail. Not knowing how we made our mistake we marked it up as one of the mysteries of life. Today, I can pull up Google Maps and show anyone who cares that the sign, in the exact same spot, is still pointing to the wrong road.

Above: In search of the right trail, we push our bikes through bogs.

Below: Fully loaded bikes are both heavy and uncomfortable to carry.

Back on track

Now on the right trail, we were able to make better time riding our bikes along beautiful lakes and slowly climbing our way to the pass. We stopped and shot photos of landscapes and each other from time to time. We’d even stopped a few times for my complicated self-timer shots where I’d set the camera up to capture the two of us riding through the environment.

Tim, on The resurrection Trail as it was meant to be ridden; this only lasted a short while.

We had thought that the 40-mile trail might be doable in a single day, but with our poor start, it was beginning to seem unlikely. As we approached the pass the trail got steeper and we had to resort to pushing our bikes; made slightly less easy due to the large panniers hanging off the sides. The pushing got harder when we hit snow. Did I mention we had chosen the month of May for our crossing because we thought it might be more picturesque with snow-packed mountains in the background? That decision was coming back to haunt us in a way we never imagined. May in Alaska was not looking like the spring we were familiar with, but a lot more like winter.

Pushing the bikes up to the pass became more difficult in the heavy winds.

After hours of pushing, we came upon a ski shelter just as the sun was setting. Tim and I usually took great pride in finding quality camping spots and not relying on shelters, but this was a special situation. After 20 miles of traveling, about 10 of it pushing, most of it uphill, and much of it through snow, we were exhausted. The shelter was a small token of good fortune, so we took it. After a hot meal we curled up in our sleeping bags and hoped the rats wouldn’t get to our food while we slept soundly for the night.

Sheltered from the weather we contemplated our situation over a hot meal.

John (left), Tim (right).

A new day

In the morning we were greeted by a fresh layer of snow. The route ahead looked completely covered in deep snow, and the top of the pass was hidden around a bend in the mountains. It could be argued at this point that the safe decision would be to go back the way we came, get on the road and forget about the trail. That just didn’t sound all that appealing to us. We’d invested so much to get to this point, it felt a shame to toss it away. Surely we could push on and trudge our way a few miles to the top of the pass. And certainly after the pass, things would get better and we could coast our way down the other side.

Pushing the bikes up to the pass was made more difficult by wet snow collecting in the spokes.

Tim (above), John (below)

Recharged after our nights rest and a hot breakfast we headed uphill, stopping to photograph our struggles along the way. While I had two Nikon SLRs with me, I used my third camera for most of my photography on this day. One of my favorite cameras of all time, the Nikon Action Touch was an underwater, bullet-proof tough, point-and-shoot with a sweet 35mm f/2.8 lens. The camera was perfect for a day like this: windy, wet and rough.

To sum up this new day on the pass, it was torture. The snow became so deep we were no longer able to push the bikes. We resorted to removing the panniers, and shuttling the equipment forward. We first moved the bags 100 yards ahead, then would return for the bikes. It was not lost on us that we were tripling our distance. This type of travel would have been much easier if we had hiking boots, but we were cyclists and only had our bike shoes designed for clipless pedals. Our shoes, besides not being all that comfortable for walking, were not designed for snow travel and as a result our feet were cold and wet for the entire day.

John, plowing the snow with the panniers.

Even in tough times like this I was keen to keep on shooting photos. It was a hard day, but I wanted to make sure it got recorded. The photos that I did take weren’t great in a traditional way, but I believe they helped tell our story. At this point we still felt we were on top of the situation. We were certainly cold and tired, but we were feeling strong, and slowly but surely still making progress.

Survival mode

When the winds picked up and it started to snow, we both knew right away that the situation had just gotten serious. The firm grip we felt we had on the situation, began to slip away. With our new situation becoming clear, I started preparing for the worst. Without hesitation I put the Action Touch away and focused on our immediate state of affairs.

My last shot before devoting all energy into escaping the situation.

We were hiking through a high mountain valley between two taller mountain ranges. The wind raced along the valley floor and there was absolutely nowhere for us to take cover. Although we tried to continue on, the winds became so fierce that we decided it was safest to bunker down. With no protection from the wind, we propped the bikes up in the snow and piled the panniers against them to create a wall. On the back side of our wind brake we used our bike helmets to dig down into the snow creating a small ditch for us to crawl into. We pulled out our sleeping bags and tent and wrapped them around us to protect us from the snow and the wind.

With the wind howling and the snow piling up, our conversation was short and to the point. The immediate problem was the cold. We had thermals, fleece and gore-tex but, with bike shoes, our wet feet were cold to the bone.

The route forward was clear, but the distance was not. Our maps, more for biking on the roads, did not show the area in great detail. We had food and a stove and could melt snow for water. But trying to start the stove in this wind was a useless endeavor. The wind also made erecting the tent a no go. It came down to two options: the first was to wait out the storm then erect the tent and start the stove, the second was to push on hoping to round the bend and seek refuge in the valley somewhere ahead. We huddled and snacked on a few energy bars while we made our decision. I don’t know how long we sat there, perhaps an hour, maybe two. In that time of waiting I had a lot of thoughts, some not very pleasant. All the while the wind continued to beat on us while the snow continued to pile up.

Our escape plan

In Alaska, it’s possible for a storm like this to go on for days. We eventually decided that staying any longer would make it harder to escape and possibly endanger our lives. We chose to push on and try to make it to a safer location. As we ate and drank as much as we could, we developed a detailed plan on how to pack everything up and move on.

Mustering all of our energy we gathered our things, packed them up and began again. We continued to shuttle our gear as before; one trip with the bags, one with the bikes. Trudging through the snow now was a bit harder as it was deeper. The progress was interminably slow. We could see a quarter or half mile ahead at a time, but it would take seemingly forever to travel that distance.

Eventually we started to round the turn in the valley were the wind wasn’t striking us head on. As the snow depth lessened and the wind lowered to a mild roar, we gained a little confidence. But it was hours before we could even put the bags on the bikes and push it across the land.

A brighter outlook

We eventually made it to a lower elevation where snow was only in patches. On some sections of trail we could coast downhill. The problem was that the trail was so beat down it looked more like a narrow ditch. The panniers on our bikes would get caught on the side and we’d come to a sudden halt. As frustrating as it was, it was a big improvement to our previous situation.

Stuck in a rut; a path not built for a bike.

We went as fast and as far from the pass as we could before dark. Finding an adequate campsite, we made a ridiculously large and, likely, illegal fire. We cooked double portions and had double the chocolate for dessert, while we warmed our tortured feet by the fire. We had made it out.

Alaskan test

At the time, we weren’t clear where we had made one specific mistake. Like many who encounter problems in the wild, it usually isn’t a single problem, but a series, that takes you off course.

While I wish that I had more photos to tell the story, I just didn’t have it in me. Photography brings me joy and happiness and when I’m experiencing pain and fear, well, the two don’t mix very well. I guess it’s good that I didn’t become a war photographer.

The next day we completed the 40-mile trail and left a lengthy and interesting statement in the logbook at the trailhead. With the bikes on pavement again we continued onward, meeting up with our previously planned route that would take us another 1200 miles across Alaska. We were a bit more cautious and stuck to the plan for the remainder of the adventure.

Unsurprisingly, we were the first cyclists to make the crossing this year.

Finishing our trip in Prudhoe Bay we looked back at Resurrection Pass as our Alaskan test. While we passed the test, I can’t say that I would give us high marks for style. I did end up with a bag full of shot rolls of film from documenting our trip. One particular day doesn’t have the photos I wish it did; I’m just glad that I’m still here to have that regret.

Only 1200 miles to go.

John Greengo (left) with his adventure buddy, Tim (right)

Become part of John’s inner circle

Sign up for the newsletter here – it’s free.

Want to become a better photographer?

Check out John’s selection of photography and camera classes here.